显示器色彩特性文件¶

sRGB 色彩空间¶

sRGB 几乎是所有消费级影像相关人士公认的标准色彩空间。1996 年,惠普(Hewlett-Packard)和微软(Microsoft)提出将 sRGB 作为消费级应用的标准化色彩空间。他们的初始提案是这么说的:

惠普和微软建议在微软操作系统、惠普产品和互联网中加入对标准色彩空间 sRGB 的支持。这个色彩空间的目的是补充现有的色彩管理策略,提供第三种处理操作系统和互联网颜色的方法,用简单且可靠的设备无关颜色定义,确保良好的画质和向后兼容,同时尽量减少传输和系统开销。这个基于色度学的 RGB 色彩空间非常适合阴极射线管(CRT)显示器、电视、扫描仪、数码相机和打印系统,软件和硬件厂商支持它的成本也很低。

目前,国际色彩联盟(ICC)通过给图像附上输入色彩空间的配置文件,确保颜色从输入到输出的空间被正确映射。这对高端用户很合适。但有大量用户并不需要这么高的色彩质量,也有很多文件格式压根不支持嵌入色彩配置文件,还有很多场景让用户不愿意给文件附上额外数据。这时候,一个通用的标准 RGB 色彩空间就变得有用且必要了。

一个通用的标准 RGB 色彩空间通过把各种标准和非标准的 RGB 显示器空间合并成单一的标准 RGB 色彩空间,解决了这些问题。这样的标准能大大提升桌面环境的颜色保真度。比如,如果操作系统厂商支持这个标准 RGB 色彩空间,输入和输出设备厂商只要支持这个标准,就能轻松自信地在最常见场景下实现颜色沟通,不需要额外的色彩管理开销。

总结一下,sRGB 这个如今几乎被全球采用的色彩空间,目的是让消费者更省心(不用操心色彩管理)、让厂商更省钱(不用担心消费级数码相机、扫描仪、显示器、打印机等的兼容性),以及让网络显示更方便(不用管嵌入和读取 ICC 配置文件,直接假设是 sRGB 就行)。

那既然 sRGB 这么好用,干嘛还要用其他色彩空间,费劲去操心色彩管理的问题?

sRGB 是为 1996 年后生产的消费级显示器和打印机设计的,目标是让颜色在这些设备上都能轻松显示和打印。它包含的颜色范围(专业术语叫 色域 )是“最低公分母”,比我们在现实世界能看到的颜色少得多,也比现在数码相机能捕捉的颜色少,比现代打印机能打印的颜色少,甚至比现在开始进入消费市场的新款广色域显示器的色域小得多。简单说,sRGB 的色域太小了,没法充分利用今天消费级设备能呈现的更广颜色范围。不过反过来,如果你压根不打算在数字影像工作流程里用更广的色域,那确实不用操心非 sRGB 颜色空间和那些复杂的色彩管理问题。

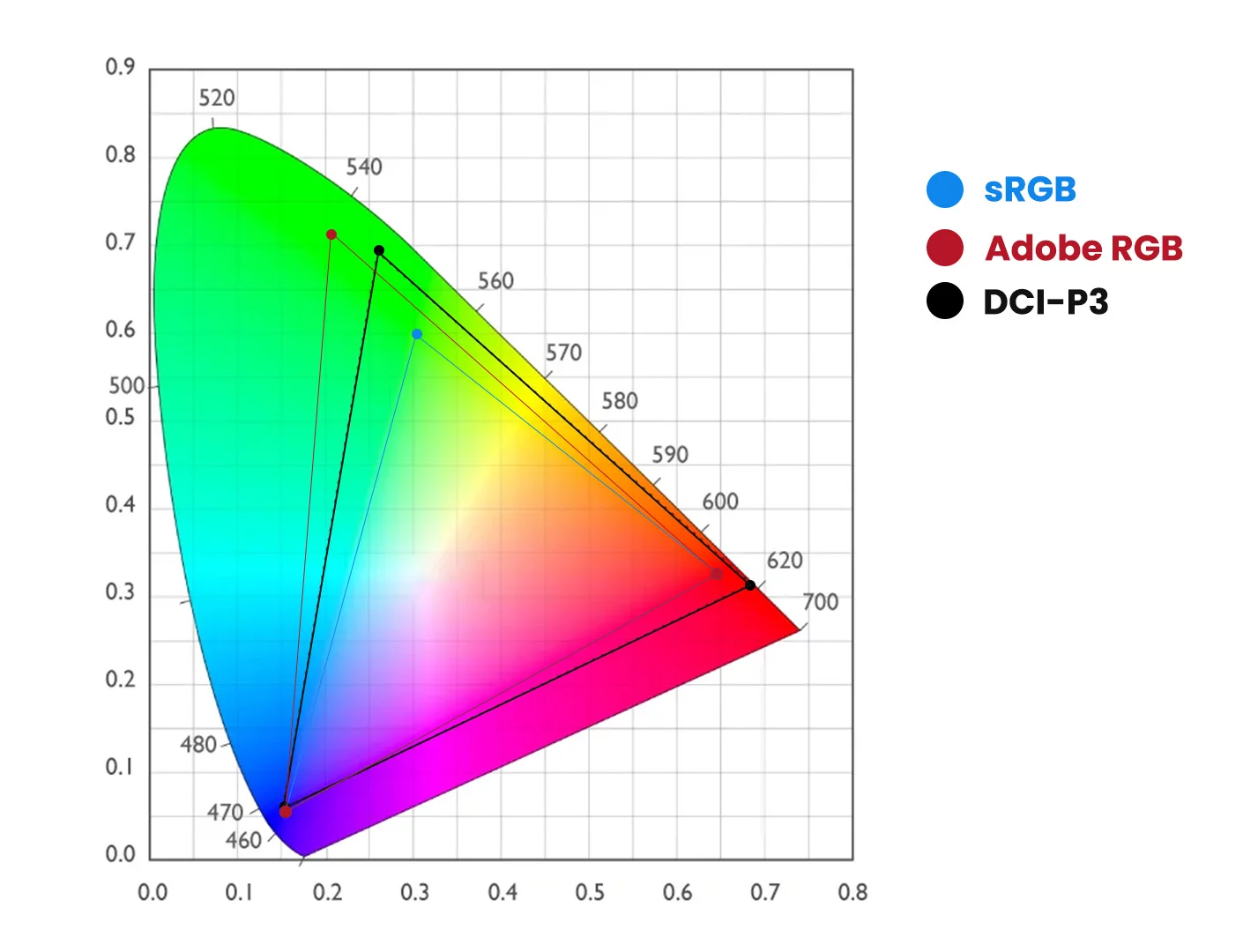

下图展示了一个直观的对比,把 sRGB、Adobe RGB 和 DCI-P3 的色域跟我们在现实世界能看到的颜色范围放在一起。这张图用二维方式表示了人类能看到的所有颜色(那个马蹄形区域)和三种色彩空间包含的颜色(那些小三角形区域)。

sRGB、Adobe RGB 和 DCI-P3 色彩空间的色域对比,sRGB 是 LCD 显示器的默认色彩特性文件¶

有意思的是,这张图片本身嵌入的就是 sRGB 色彩特性文件,所以它展示的颜色并不能完全代表其他色彩空间的全范围。

为你的显示器创建色彩特性文件¶

如果你选择全程用 sRGB 色彩空间,是不是就不用校准显示器了?不管你是不是只用 sRGB 的色域,答案都是:必须校准!因为 sRGB 的前提是你的显示器已经校准到 sRGB 的标准。

如果使用的是没校准的显示器,会有几种后果,没一个是好的。每个显示器(无论校准过或没校准)都有一个原生的(未校准的)白点,用色温(开尔文度数)表示。白点就是你在屏幕上看纯白(RGB 值在 8 位下全是 255,比如网页或文档的纯白背景)时的颜色。你可能觉得“白就是白”,但如果你把几台校准到不同白点的显示器摆一起,就会发现白点色温越高,屏幕看起来越偏蓝;色温越低,越偏黄。

你可以自己试试,用显示器的控制按钮把色温调高或调低,感受一下屏幕变蓝或变黄的变化(试完记得调回原设置!)。你的眼睛很快会适应固定的白点,但调整色温时,蓝黄变化会很明显。如果没校准的显示器偏蓝,你编辑图片时会过度补偿,结果在校准正常的显示器上看,你的图片会偏黄、显得太“暖”。反过来,如果显示器色温太低(比如 LCD 原生色温大约 5500K,而 sRGB 假设是 6500K),偏黄的屏幕会导致你编辑的图片在正常显示器上看起来偏蓝、太“冷”。

校准显示器不只是设置白点,还要搞定黑点、亮度(发光强度)和伽马(传输)函数。如果黑点设太低,显示器太暗,你会过度补偿,编辑出的图片在正常显示器上会显得褪色、没活力。相反,如果黑点设太高,你的图片在正常显示器上会显得太暗、饱和度过高。

如果你把显示器亮度/对比度设太高,你会觉得图片很有“冲击力”,但在正常校准的显示器上,这些图片其实没那么鲜艳,而且高亮度会让你的眼睛不舒服,还会加速 LCD 屏幕的老化。

F12 快捷键可在图像编辑器和 digiKam 所有缩略图视图中开关色彩管理¶

如果你的显示器伽马值设置不对,暗部到亮部的色调变化就会出问题。比如,阴影或高光可能会被过度压缩或拉伸,导致你在编辑时往反方向过度补偿。结果呢?在校准正常的显示器上看,你的阴影可能太亮或太暗,高光也可能太暗或太亮,整个图片的色调看起来像是被“挤”得太紧了。更别提如果显示器的内部颜色通道增益设置错误,那问题就大了!你编辑时为了“纠正”颜色,可能会让图片偏绿、偏洋红、偏橙……这些色偏在校准正常的显示器上会特别明显,简直让人抓狂。

哪怕你的显示器没校准,你也可能会惊讶地发现,同一张图片在你家显示器上看起来跟在其他显示器(比如你家另一台显示器,或者朋友、邻居的显示器)上完全不一样。通常,在一台没校准的显示器上编辑的图片,换到另一台没校准的显示器上,效果会天差地别。你可以买一台已经校准好的显示器,或者买个分光光度计来自己校准显示器、创建色彩特性文件。

你可能会惊讶,校准显示器和给显示器做色彩特性文件居然不是一回事!校准(calibration)是通过调整显示器的控制选项或其他物理方式,让设备达到某个定义好的状态。比如,校准显示器就是用显示器的控制按钮和显卡设置,调整 白点 、 黑点 、 亮度 和 伽马 到标准值。

相比之下,创建色彩特性文件(profiling)是个测量过程,不会对设备做任何调整或改变,而是生成一个文件,精确描述设备的颜色和色调特性。这个文件就是 ICC 色彩特性文件 。它包含了设备色彩空间到标准绝对色彩空间(在 ICC 色彩特性文件中叫配置文件连接空间)的转换函数、设备的 白点 、黑点 、 原色(色彩空间) 等信息。显示器通常是在校准后的状态下创建色彩特性文件的。

严格来说,校准显示器不算色彩管理的一部分。但显然,一个正确分析过的显示器是色彩管理流程的先决条件。这份手册不深入讲如何校准和分析显示器,但 Argyll 的文档非常棒,强烈推荐阅读。想用 Argyll 软件校准或创建色彩特性文件,你得有个分光光度计(有时候叫“蜘蛛”),用来测量校准/分析软件(比如 Argyll)投到显示器屏幕上的颜色块的 RGB 值。Argyll 官网有最新的支持分光光度计列表。

校准显示器¶

网上有很多不用分光光度计校准显示器的方法,靠的就是“眼球校准”。这些方法总比完全不校准好,凭你的眼力和显示器情况,效果也能凑合着用。但说实话,眼球校准没法完全替代用分光光度计做的专业校准和分析。别被分光光度计吓到,校准和分析显示器虽然一开始看起来复杂,其实不难。分光光度计的价格也不贵,100 欧元以下就能搞定(如果你买更贵的型号,注意别花冤枉钱买一堆 Linux 上跑不了的厂商软件,硬件好就行)。

Argyll 的文档会手把手教你怎么校准显示器、创建色彩特性文件,不用你先去啃一堆色彩管理理论。而且,如果有一天你对色彩管理了解多了,想为特定用途做个更精细的显示器色彩特性文件,Argyll 的强大功能绝对能满足你。

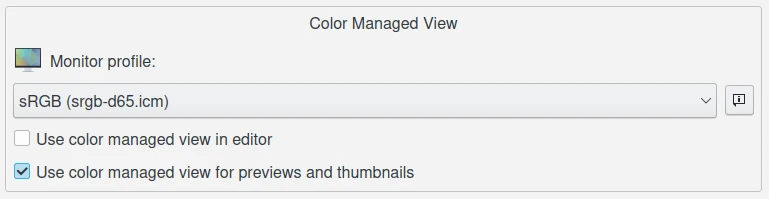

假设你决定全程用 sRGB 色彩空间,校准完显示器后,digiKam 里要 按哪些按钮 ?如果你的显示器已经校准到 sRGB 标准,而且你只用 sRGB 色彩空间,那你可以直接在 digiKam 里禁用色彩管理。你不用特意告诉 digiKam 用哪个显示器色彩特性文件,因为 digiKam 默认把 sRGB 当做显示器色彩空间配置文件,也不用告诉 digiKam 用色彩管理流程,因为它默认会用 sRGB 来处理你的相机、打印机和工作空间。

digiKam 色彩管理设置页面中的显示器色彩特性文件设置¶

但如果你想迈出色彩管理的第一步,那就去 ,在“行为”选项卡里启用色彩管理,然后切换到 色彩特性文件 标签,选 sRGB 作为你的 显示器色彩特性文件 、 相机色彩特性文件 、 工作空间色彩特性文件 和 打印机色彩特性文件 。如果你还用 Argyll 生成了一个显示器配置文件(最好是在校准显示器后生成的),比如叫 mymonitorprofile.icc ,那就告诉 digiKam 用这个色彩特性文件代替 sRGB 作为显示器色彩特性文件。

显示器色彩特性文件的存储位置¶

显示器色彩特性文件在 Windows,MacOS 和 Linux 上存储的位置各不相同。

在 Windows 上,默认搜索路径包括:

C:\Windows\System32\spool\drivers\color\

C:\Windows\Spool\Drivers\Color\

C:\Windows\Color\

在 macOS,默认搜索路径包括:

/System/Library/ColorSync/Profiles/

/Library/ColorSync/Profiles/

~/Library/ColorSync/Profiles/

/opt/local/share/color/icc/

/Applications/digiKam.org/digikam.app/Contents/Resources/digikam/profiles/

~/.local/share/color/icc/

~/.local/share/icc/

~/.color/icc/

在 Linux,默认搜索路径包括:

/usr/share/color/icc/

/usr/local/share/color/icc/

~/.local/share/color/icc/

~/.local/share/icc/

~/.color/icc/

在 Linux 和 macOS 下,你自己的 ICC 特性文件通常位于 home (用户名)文件夹下的 ~/local/share/color/icc 这个文件夹。

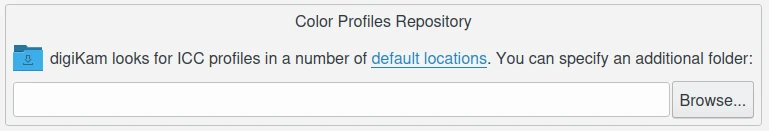

在 digiKam 里你可以自行个人色彩特性文件的存放位置¶

环境光线与显示器¶

问:我工作台附近的灯光、墙壁、天花板、窗帘和家具颜色重要吗?答:当然重要!好的光线环境是正确编辑图片和比较屏幕图像与打印效果的前提。如果工作台附近的光线太亮(或太暗),显示器上的颜色就会显得太暗(或太亮)。如果工作间的灯具光线 显色指数(CRI) 低(也就是没用全光谱灯泡),或者光线来自窗户,会随着天气和时间变化(更糟的是,可能会被有色窗帘过滤),又或者墙壁和天花板的颜色在显示器上造成色偏,那你在编辑图片时,可能会去“纠正”一些根本不存在的颜色偏差。

虽然家庭和谐很重要,但我们最好的建议是:把墙壁和天花板刷成中性灰色,把窗户遮住,穿中性颜色的衣服,用合适的灯泡和灯具设置适当的光线强度。