相机配置文件¶

使用相机色彩特性文件¶

很多顶尖的专业和业余摄影师都会选择直接保存相机生成的 JPEG 文件,并且全程用 sRGB 色彩空间工作。如果你也满足于这种方式,完全没问题!但如果你想用更大的色彩空间,或者想玩转 RAW 文件(即使最终还是输出 sRGB 图像),那就接着往下看吧。

如果你在读这份手册,估计你已经在用数码相机拍 RAW 文件了,而且可能正头疼于色彩管理的“神秘魔法”,想知道怎么从 RAW 文件搞出一张好看的照片。接下来,你需要一个合适的相机配置文件来处理你的 RAW 文件。但先来回答一个你可能真正想问的问题:

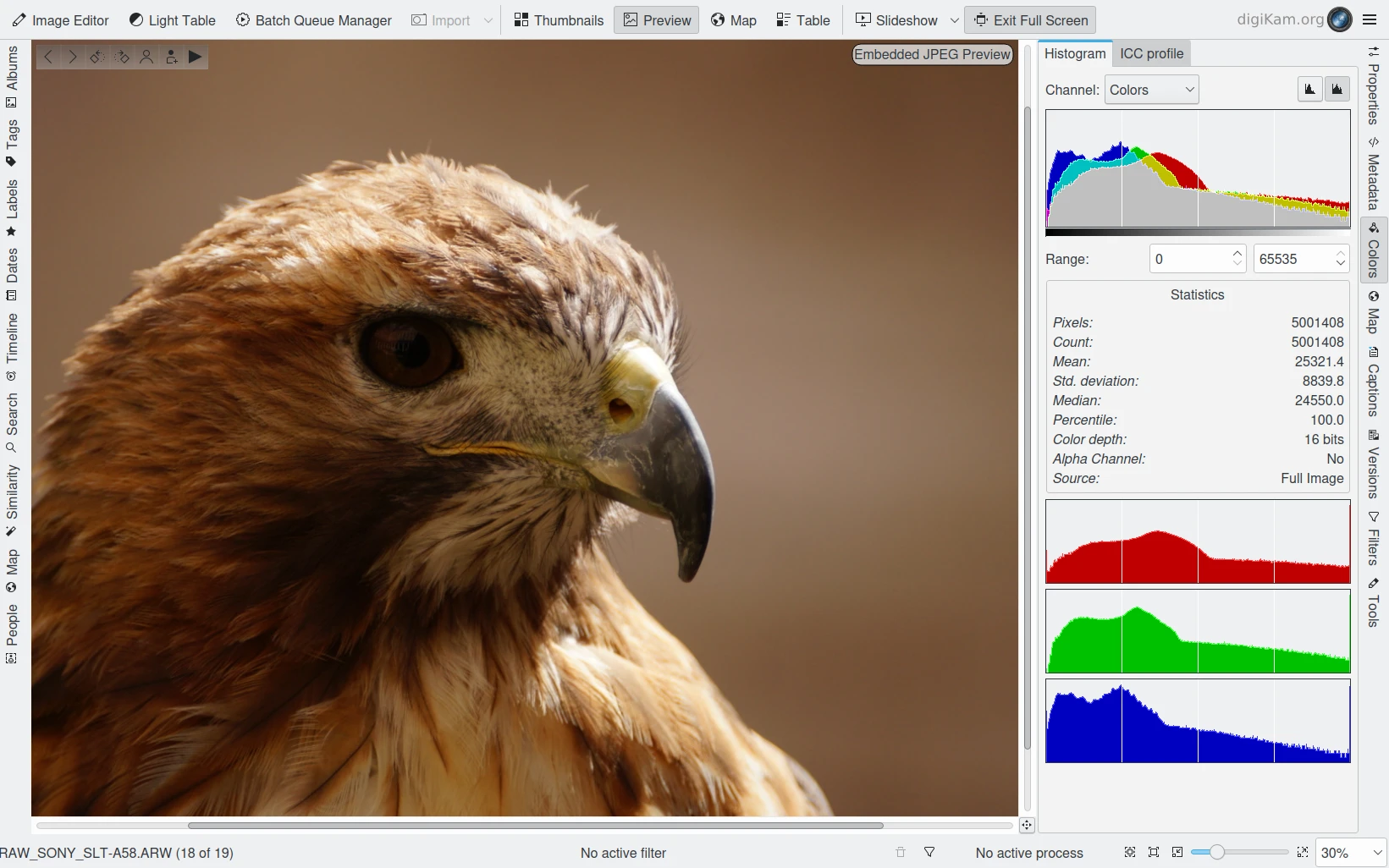

digiKam RAW 预览使用 嵌入的 JPEG 图像¶

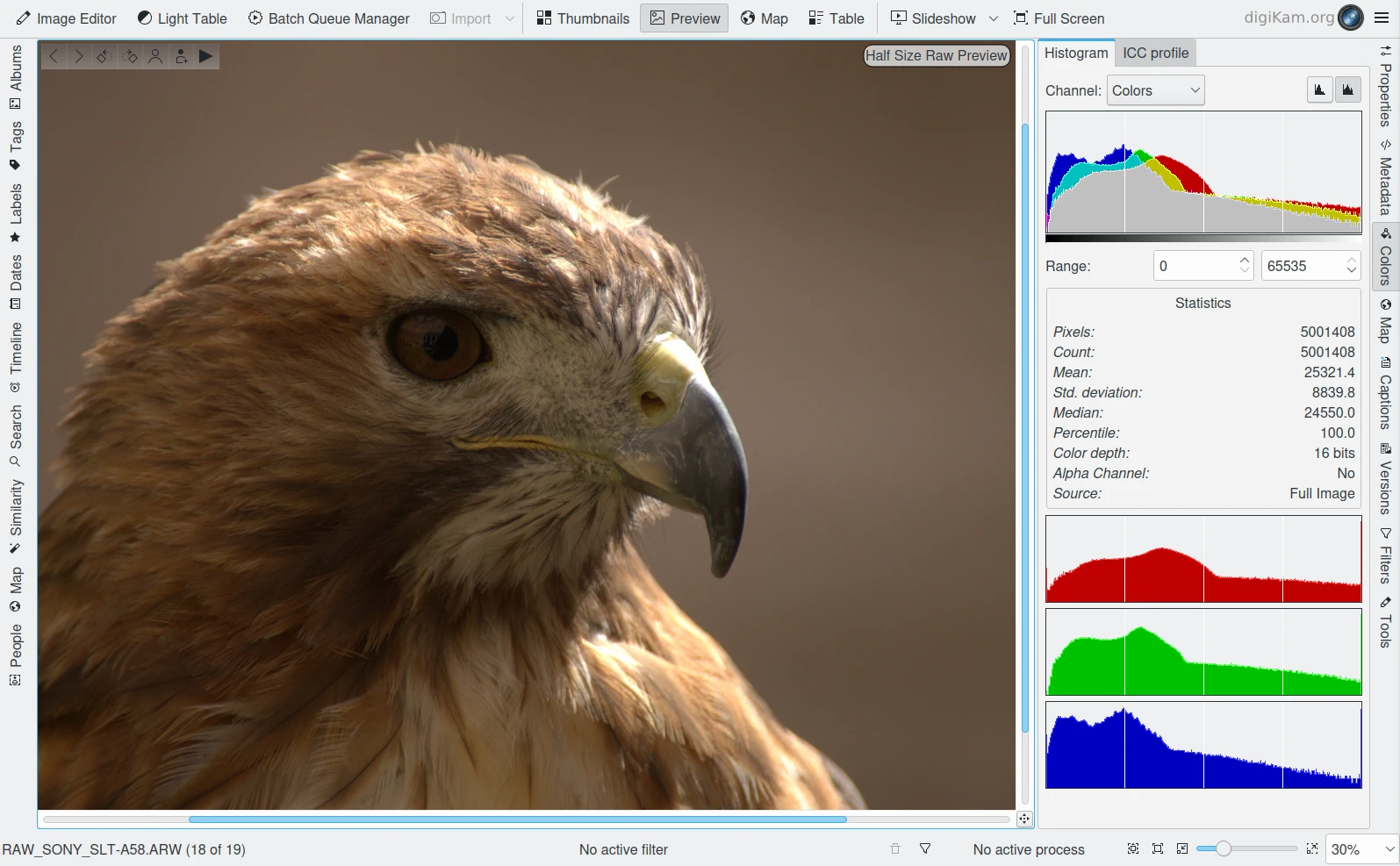

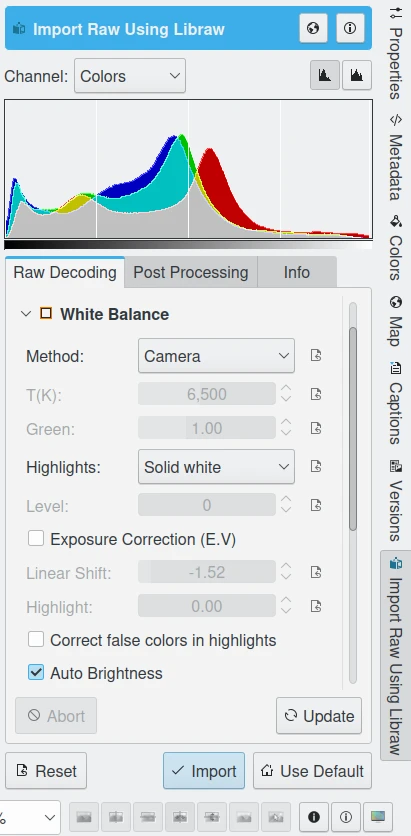

Digikam Raw 预览,使用 8 位色深、半尺寸去马赛克、 ** birinear ** 方法¶

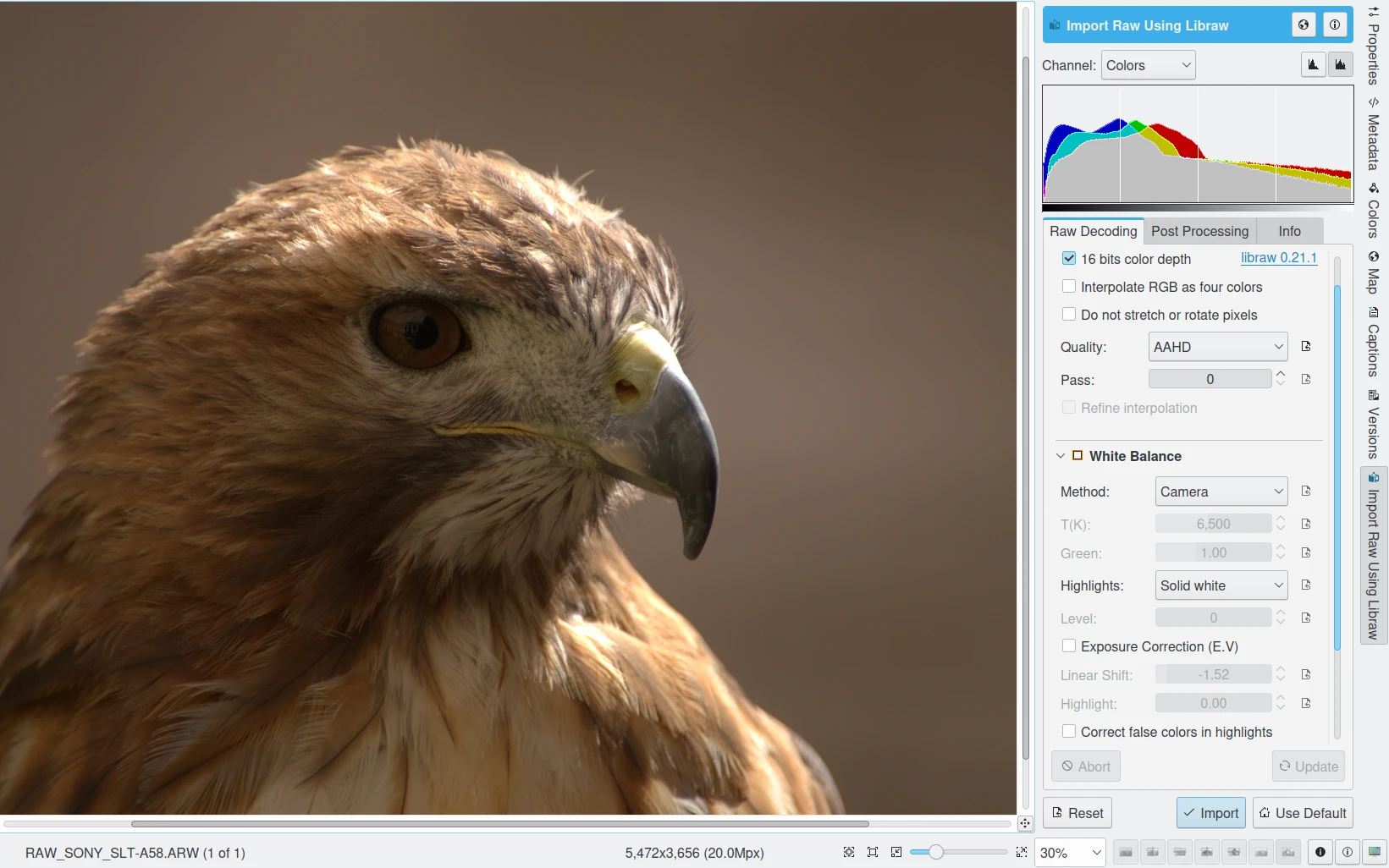

digiKam 图像编辑器的 RAW 导入工具,加载 16 位和 AHD 方法去马赛克的 RAW 文件¶

为什么像 Libraw 这样的 RAW 转换器生成的图像,看起来跟 digiKam 显示的嵌入式预览图不一样?其实,所有数码相机的图像一开始都是 RAW 文件,不管你的相机能不能让你保存 RAW 文件。如果你让相机保存 JPEG,相机内部的处理器会把 RAW 文件转成 JPEG。那个嵌入的预览图,其实就是如果你设置相机直接输出 JPEG 时,图片最终的样子。

以佳能为例,他们提供了几种“照片风格”——比如中性、标准、人像、风光等等——这些风格决定了 RAW 文件会被怎么处理,不管是在相机里直接处理,还是事后用佳能的专有软件处理。这些软件会给你一些额外的控制权,但处理方式还是基于你选的照片风格。大多数佳能照片风格会加个很重的 S 型曲线,再加上额外的颜色饱和度,让照片看起来更有“冲击力”。即使你选了“中性”风格(佳能里改动色调最少的选项),并且在佳能 RAW 处理软件里把对比度、饱和度、降噪和锐化都调到最低,如果你仔细看,还是会发现图片被悄悄加了 S 型曲线和阴影降噪处理。

digiKam 用的 Libraw 来把 RAW 文件转成图像文件,它不会给你的图片色调加 S 型曲线。 Libraw 直接给你相机传感器记录的真实光暗信息。它是少数几个能给你“场景参照色调”的 RAW 处理工具之一。Libraw 生成的场景参照图像看起来会比较“平淡”,因为相机传感器记录光线是线性的,而我们的眼睛和大脑会不断互动,自动调整对场景中亮部和暗部的感知,某种程度上就像给场景加了个 S 型曲线,让我们更容易聚焦在感兴趣的区域。

嵌入的 JPEG 预览图看起来比 Libraw 的输出好看多了,那场景参照色调有啥用?当你拍照时,估计心里已经有最终想要的画面效果了吧。如果你的图片没被提前“加工”过,你会更容易实现那个效果。一旦佳能(或尼康、索尼等)给你的图片加了专有的 S 型曲线、阴影降噪、锐化等处理,你的阴影、高光、边缘细节等就已经被压扁、裁剪、砍掉,甚至弄得乱七八糟。你丢掉了信息,尤其是阴影部分的信息,再也找不回来——即使是 16 位图像(实际上可能是 12 位或 14 位,只是为了电脑处理方便编码成 16 位)。一开始的信息量就没那么多!

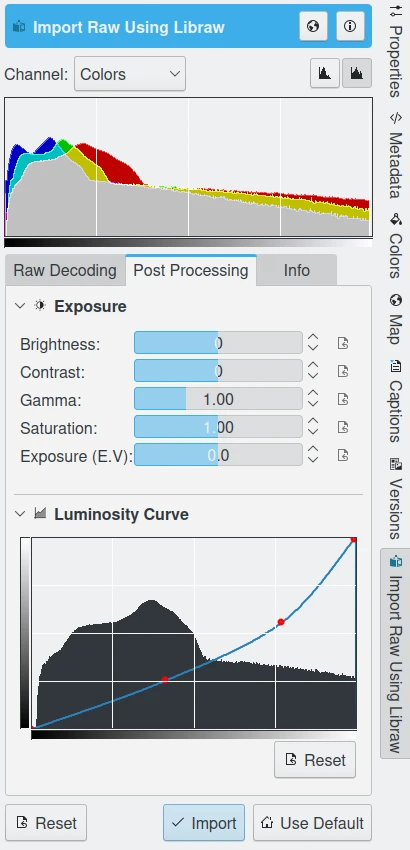

你可以用图像编辑器的导入工具,在去马赛克后,立即对曝光和曲线进行后期处理¶

在我看来,图像处理的精髓和灵魂就在于你如何刻意调整图像的色调、颜色、局部锐化等等,让看照片的人能聚焦到你——摄影师——在按下快门时觉得特别重要的东西上。为什么要让厂商的专有 RAW 处理软件来接管这门艺术呢?换句话说,如果你想让照片带上你自己的艺术风格, “平淡”的起点才是更好的选择 。否则,你就只能让佳能、尼康、索尼等厂商的“罐头算法”来替你解读你的照片。当然,不可否认,对很多照片来说,这些厂商的算法确实挺不错的。

但你应该能看出哪个选择更值得做,从“场景参照”的版本开始编辑照片,比直接用嵌入 JPEG 那种吸睛的效果要更有价值。不过,digiKam 和 Libraw 生成的图像看起来可能有点不一样。如果你在Libraw里设置输出 16 位文件,结果图像看起来特别暗,那可能是 Libraw 在输出图像文件前没做伽马转换。你可以在图像编辑器里手动给 Libraw 输出的文件加上合适的伽马转换,或者找一个伽马值为 1 的相机配置文件(或者自己做一个)。

如果你的图像高光部分带点粉红色,检查一下 RAW 导入工具里的 白平衡设置 ,尤其是 高光 相关的选项。

你可以用图像编辑器中的 Raw 导入工具,调整有关相机色度值的许多选项¶

如果图像不暗,但看起来怪怪的,可能是你在图像编辑器的 RAW 导入界面里选了些不太合适的设置。Libraw的界面很方便,能让你 调整 各种选项。但方便也是有代价的:首先,界面可能没提供所有选项;其次,要真正用好 Libraw 的界面,你得搞清楚那些按钮、滑块到底是干嘛用的。

相机色彩特性文件特性¶

为什么佳能和尼康的颜色看起来比 Libraw 处理的颜色更好?在颜色呈现上,佳能(以及推测尼康)的专有 RAW 处理软件确实干得漂亮。

它们的专有 RAW 处理软件搭配的相机色彩特性文件(也叫“相机颜色配置文件”),是专门为你的相机品牌和型号的 RAW 文件量身定制的,配合自家软件使用效果最佳。在 digiKam 的 Libraw 界面里,你可以尝试在 RAW 处理过程中应用佳能的相机型号专属照片风格的色彩特性文件,但出来的颜色还是跟佳能自家软件处理的不完全一样。

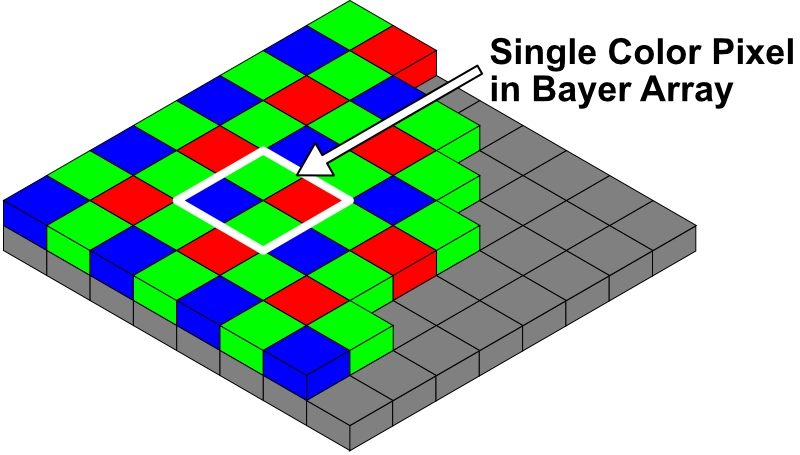

数码相机内部有数百万个微小的光传感器,通常是 CCD 或 CMOS 传感器。这些传感器天生是“色盲”的,只能记录光量的多少,不能分辨颜色。为了让它们记录颜色信息,每个像素上都盖了一个透明的红、绿或蓝滤镜,通常按照所谓的拜耳阵列排列(除了适马的 Faveon 传感器,工作方式不同)。RAW 文件其实就是一堆数值,记录了通过红、蓝、绿滤镜进入传感器的光量。

拜耳阵列:RGB 滤镜的排列方式¶

像素对光线的反应受很多相机特定因素影响,包括:传感器本身的特性、RGB 滤镜的具体颜色和透光性能,以及相机内部模数转换和后续处理的过程,这些最终生成了存储卡上的 RAW 文件。

模数转换¶

“模拟”信号是连续变化的,就像你往杯子里倒水,水量可以无限细分。而“数字化”就是把这些连续变化的信号“四舍五入”成离散的数字,方便电脑处理。相机里的光传感器是模拟的——它们根据接收到的光量积累电荷。

这些电荷随后被相机的模数转换器(ADC)转成离散的数字量。这也解释了为什么 14 位转换器比 12 位好——更高的精度意味着转换过程中丢弃的信息更少。

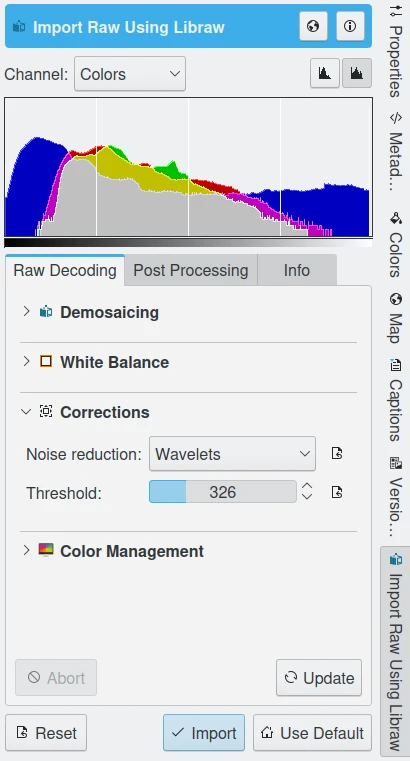

每个像素积累的电荷还会受到各种噪声的干扰,这些噪声会给 RGB 测量值带来波动,尤其在低光条件下拍的照片里更明显。digiKam 和 Libraw 的界面提供了一种基于小波的降噪功能,可以在去马赛克(demosaicing)时应用,帮你减少这些噪声的影响。

digiKam 图像编辑器的 RAW 导入工具支持去马赛克时的小波降噪¶

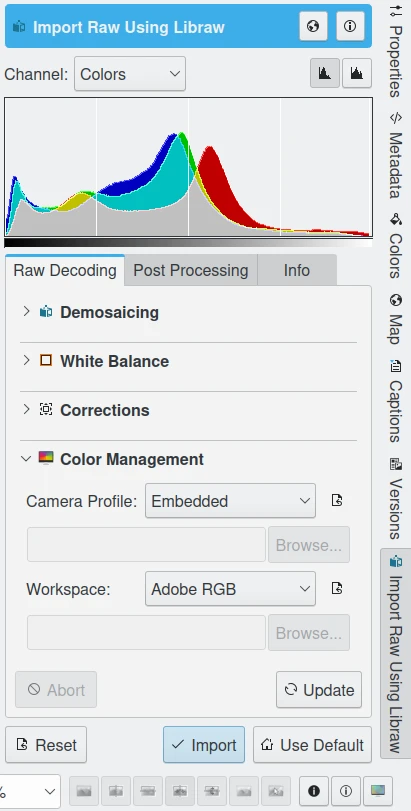

相机色彩特性文件与RAW处理¶

像 Libraw 默认使用的 AHD 去马赛克算法(想了解更多可以看看维基百科的 去马赛克 词条),核心任务是通过单个像素及其周围像素的信息,估算出落在每个像素上的光线颜色和强度。每个 RAW 处理程序都会做一些额外的假设,比如:测量的数值里有多少是真实信号,多少是背景噪声?或者传感器的像素在什么时候达到饱和?这些算法和 RAW 处理软件的假设最终会生成图像中每个像素的 RGB 数值组合。同样一张 RAW 文件,不同的 RAW 处理器输出的 RGB 数值可能会不一样。

digiKam 图像编辑器的 RAW 导入工具支持在去马赛克时调整色彩特性文件¶

获取相机色彩特性文件¶

我们真希望能告诉你“找一个现成的相机色彩特性文件很简单”,可是这只能是希望。如果你翻翻 digiKam 用户论坛的存档,可能会找到一些额外的建议。只要你不停地搜索和尝试,很有可能找到一个“够用”的通用色彩特性文件。但就像前面说的,数字影像有个让人头疼的事实:佳能、尼康等厂商提供的相机色彩特性文件,在开源 RAW 转换器上的效果不如它们自家专有 RAW 转换器好。这就是为什么专有软件得为它们支持的所有相机型号单独制作色彩特性文件。所以,你可能会最终决定,想要一个专门为你这台相机、你的光线条件和 RAW 处理流程量身定制的相机色彩特性文件。

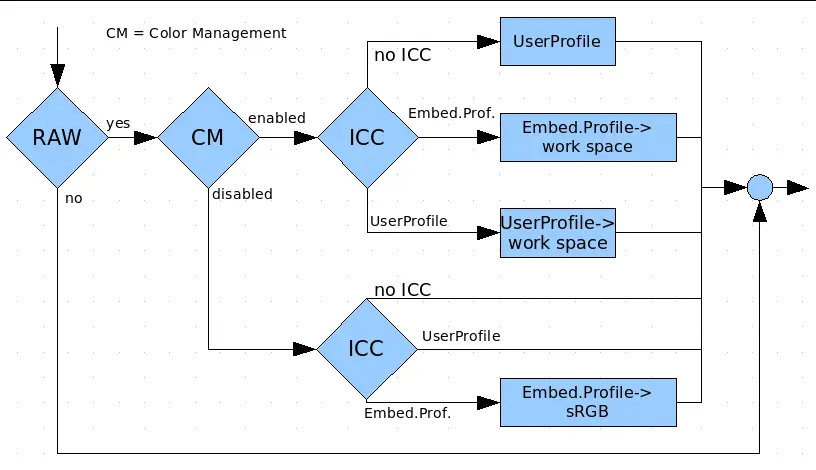

RAW 工作流程中色彩管理的逻辑草图¶

很多商业服务可以帮你制作相机色彩特性文件,当然得花钱。如果你想自己动手,可以用 Argyll 来给你的相机做色彩特性文件。自己做的话,你需要一个 IT8 色卡 ,也就是一张包含已知颜色方块的图像。买 IT8 色卡时,会附带每个颜色方块的标准 RGB 数值。

如果你打算用 Argyll 做相机色彩特性文件,记得查阅官方文档,里面有推荐的 IT8 色卡列表。做色彩特性文件的过程是这样的:你在特定光线条件下(比如夏天正午的阳光下,确保附近没东西挡光或反光影响目标)拍摄 IT8 色卡,保存为 RAW 文件。然后用你的 RAW 处理软件和设置处理这个 RAW 文件,再把输出的图像文件丢进 Argyll 的分析软件。分析软件会把你相机 + 光线条件 + RAW 处理流程生成的 RGB 数值,跟 IT8 色卡的标准 RGB 数值对比,生成你的相机 ICC 色彩特性文件。

给相机做色彩特性文件跟给显示器做色彩特性文件是一个道理。给显示器做色彩特性文件时,软件会让显卡输出特定 RGB 值的颜色方块到屏幕上,然后用分光光度计测量屏幕实际显示的颜色。给相机做色彩特性文件时,已知的颜色是 IT8 色卡上的标准色块,分析软件会比较这些色块和你相机拍出的数字图像的颜色差异。

应用相机色彩特性文件¶

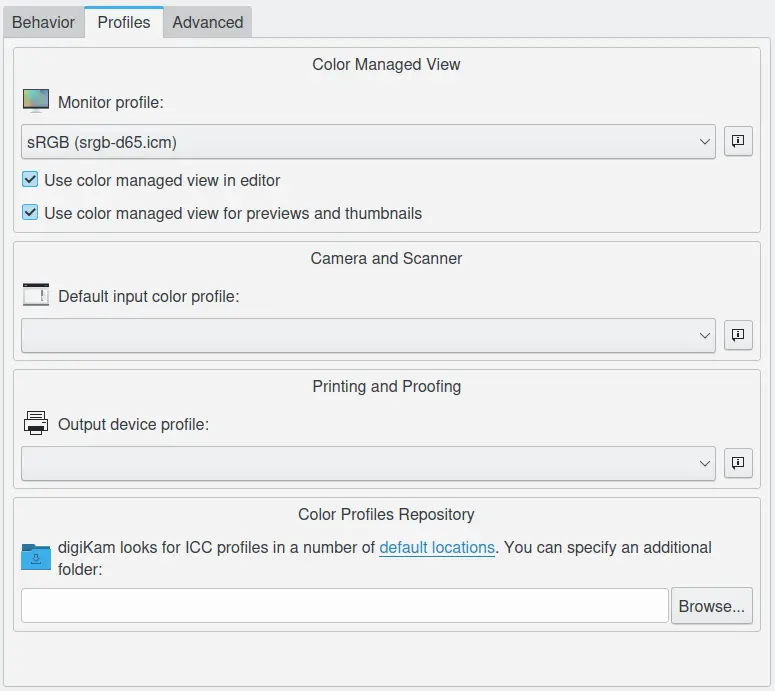

想在digiKam里设置默认的相机色彩特性文件,点开 ,然后选你想要的相机特性文件。更多详情可以看看手册里的 色彩管理设置 部分。

digiKam 中设置色彩特性文件的对话框¶

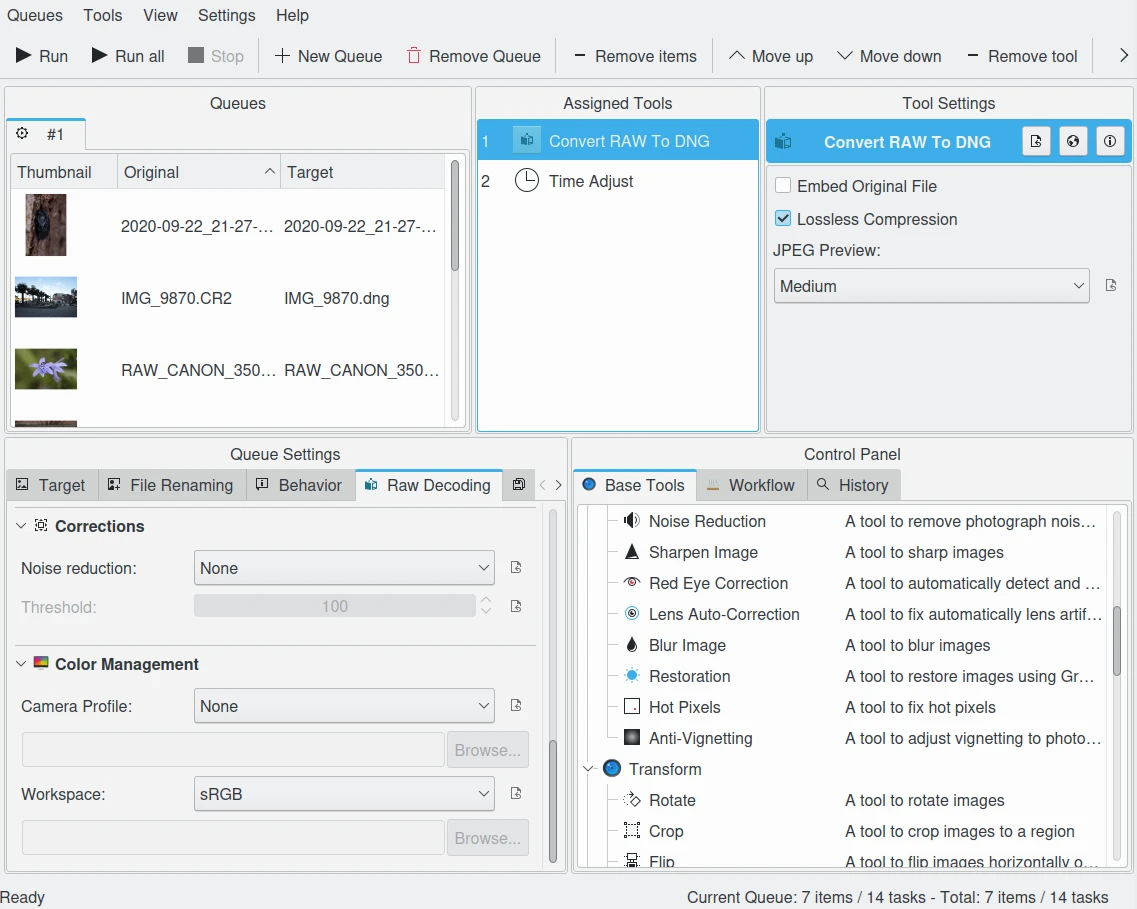

你还可以用批处理管理器,把开源 RAW 处理软件生成的 16 位图像文件转到你的工作色彩空间。

digiKam 批处理管理器的 RAW 转换工具跟图像编辑器有相同的降噪和色彩特性文件选项¶

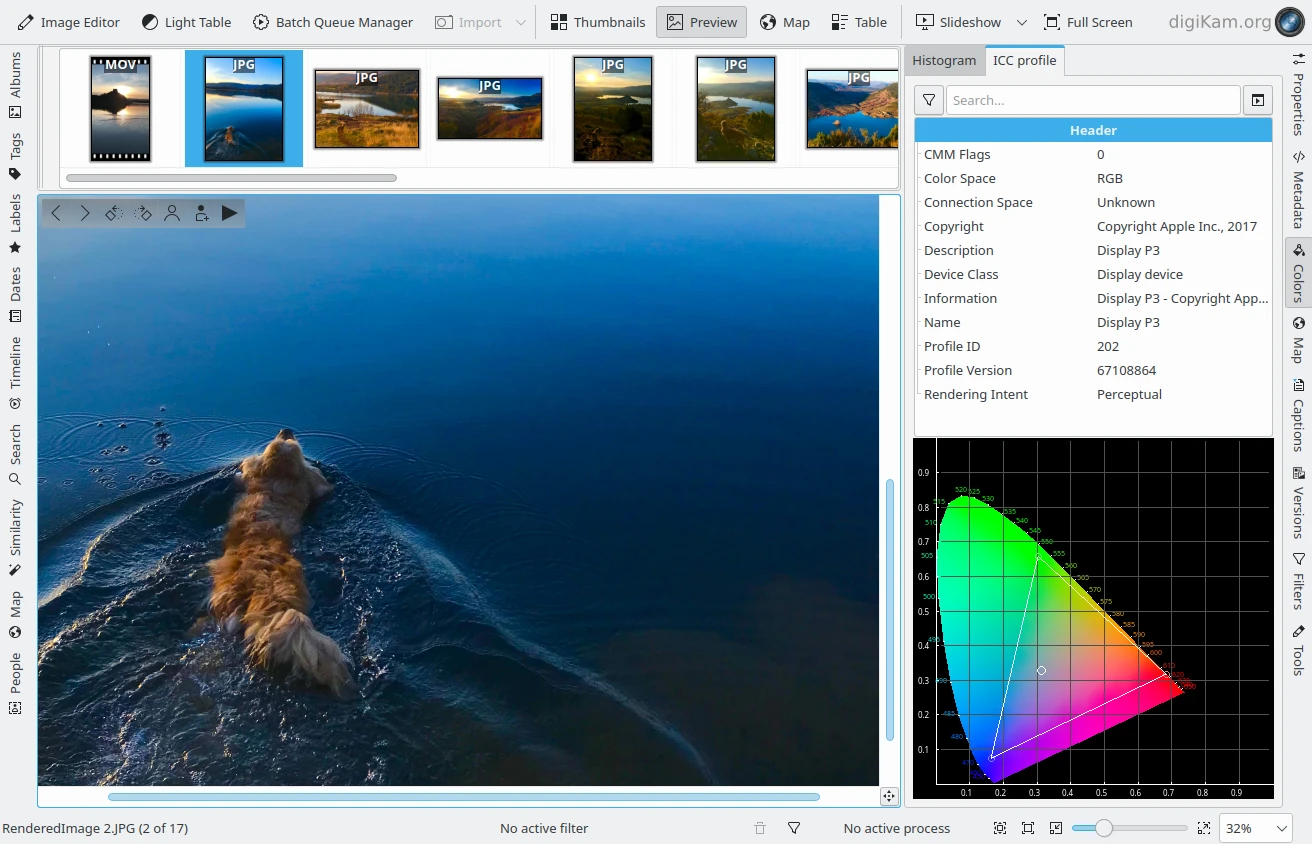

一旦指定了相机色彩特性文件,digiKam 就能在右边侧栏的“颜色”选项卡里显示选中图像的色域。

digiKam 可以从右边侧栏的颜色选项卡显示你的相机色彩特性文件¶